Getting Out the Vote for Valérie Plante

Last November 5th was Municipal Election Day in Montreal and I’m proud to say I was one of the hundreds of volunteers who got out the vote to elect Valérie Plante as Montreal’s first female mayor and the leader of Projet Montréal. However unlike most volunteers who were making phone calls, going door to door or driving electors to polling stations, I was at the campaign headquarters in front of my computer writing SQL queries and interpreting data from a real-time web dashboard I’d built the week before. In this post I’ll explain some of what I learned through this experience about get-out-the-vote (GOTV) efforts, and a bit more about the small role I played.

Key Ingredients in Getting Out the Vote

I didn’t know much about how this is actually done before getting involved in this campaign, but through helping out campaign staff member Jacob Homel, I learned about how the process works from the inside. Voter turnout in Montreal municipal elections is very low; just above 40% of the roughly 1.2 million electors actually vote, so even if people liked our candidate, they would need reminders and nudges to actually get out the door, get to the polling station and cast a ballot. The main tools at the campaign’s disposal to do this on election day were phone calls and knocking on doors, which is quite labour-intensive, requiring three key ingredients: volunteers, preparation and efficiency.

Projet Montreal is a grassroots party focused on quality-of-life issues and the environment, which makes for lots of motivated volunteers like myself! I don’t know the exact number of volunteers we had on the ground on election day but 400-500 is a decent estimate: we had 103 candidates standing for election, and there were 3,373 polling stations in 58 districts to observe, phone banks to wo/man, vehicles to drive etc.

In terms of preparation for election GOTV efforts, throughout the election season the campaign team ran a voter identification and canvassing program. This meant running phone banks and going door to door to have conversations with electors and find out how they felt about Valérie Plante and how likely they were to vote for her. This wasn’t surveying or polling, where what matters is unbiased sampling and anonymous, aggregate levels of support: in this context the elector’s contact information was recorded alongside their perceived level of support. Throughout the campaign, the team also ran tests on support-level estimates (or ‘marks’) obtained through different methods: door-to-door, face-to-face, phone conversations, online questionnaires. This enabled them to gauge the relative accuracy of every type of mark, ensuring that we could focus our GOTV efforts on those most likely to vote for Projet Montréal, and least likely to vote for the other side.

Despite the number of volunteers available, our task on election day was daunting: canvassing efforts had reached more than 10% of electors – 135,000 people – so efficiency in our phone calls and door to door efforts was paramount. We had to avoid wasting time by phoning or visiting supporters who had already voted. All political parties know this, and so do the institutions which organize the elections: the Directeur général des élections du Québec (DGEQ) and Élection Montréal. In order to facilitate get-out-the-vote efforts on election day, the DGEQ has a process whereby polling station supervisors notify, every hour, each candidate’s representative about which electors voted at which polling station that hour. As a relative newcomer to electoral mechanics, this surprised and fascinated me when I first heard about it!

Electoral Lists and Bingo Sheets

Here’s how things work behind the scenes:

- The DGEQ manages the list of electors: who is eligible to vote in which elections in Québec.

- The DGEQ mails out to each elector a card telling them where to vote, and their polling station number. For example, my card said I should report to polling station number 76 at such and such an address.

- The DGEQ shares the list with candidates’ campaigns during the electoral cycle. This list includes electors’ names, addresses, phone numbers, dates of birth and, critically, the polling station number and the elector’s sequence number within that polling station. For example I was elector number 138 for ballot box number 76.

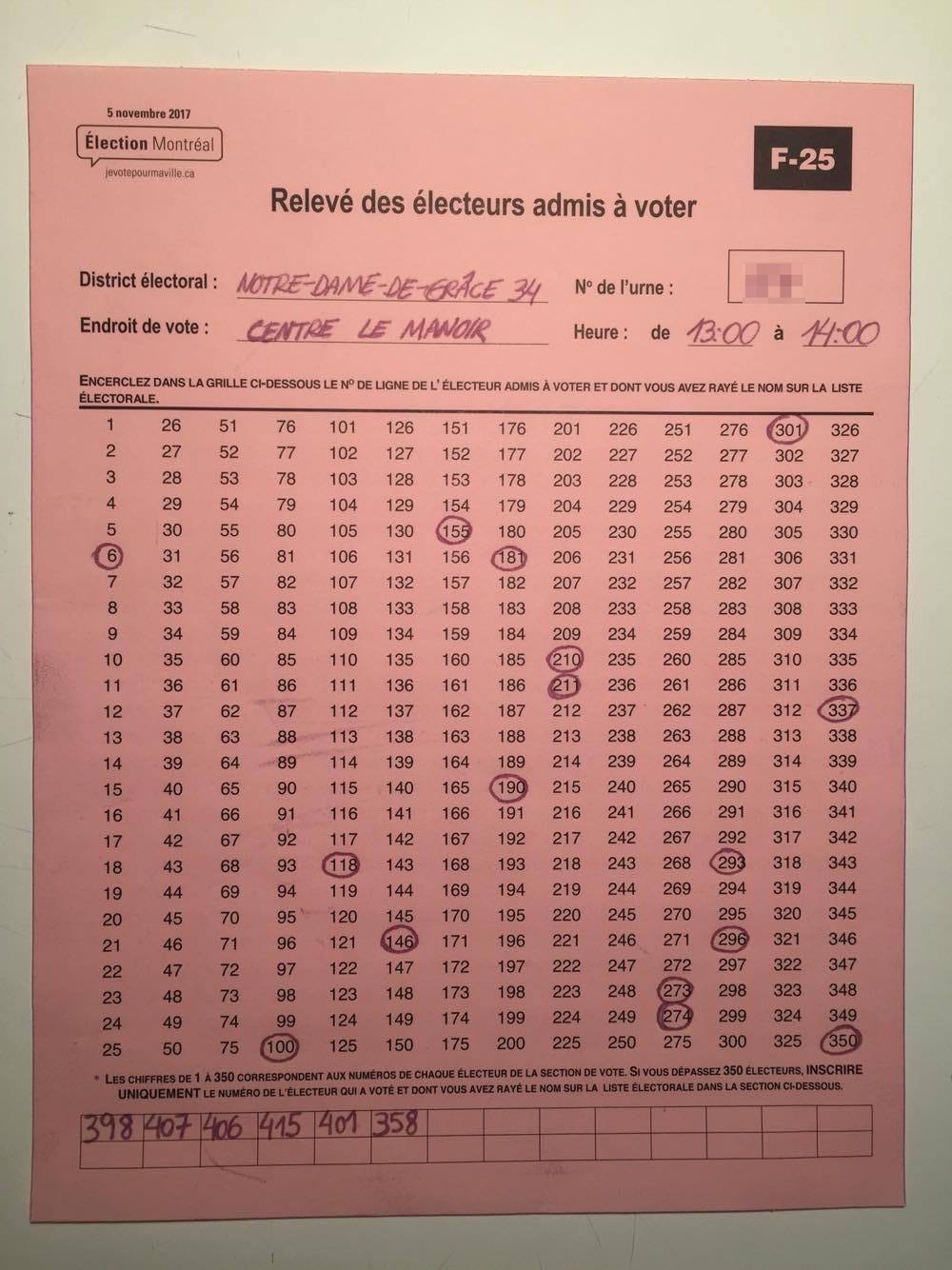

- During election day, the polling station staff crosses out the names of electors as they come and vote, and they circle the corresponding sequence number on what’s called a “bingo sheet”, which looks like the photo below.

- Every hour, each candidate or party’s representative (or ‘runner’) gets a copy of the bingo sheet for each polling station, to do with what they please. Given that polls were open for 10 hours and there were 3,373 polling stations, this means that over the course of the day, we received around 30,000 bingo sheets!

A bingo sheet

My Small Contributions

Finally we come to the problem which I was able to help tackle with my SQL queries: how to combine a stream of 30,000 sheets of paper with one list of 135,000 canvassing conversations and another list of 1.2 million electors so as to avoid contacting people who had already voted, and beyond that to help efficiently reallocate volunteer efforts throughout election day.

To begin with, a few weeks before election day, I helped Jacob merge the DGEQ list with the campaign’s internal databases in NationBuilder and our canvassing software so as to match up the real-world conversations that were occurring with the DGEQ’s rather abstract polling-station/sequence-numbers. We did this by matching names, birthdates and addresses. This sounds – and is – unromantic, but lists of 1.2 million electors are a multi-day error-prone headache in Excel, so the ability to build and test a Python data pipeline in a couple of hours came in really handy.

After that, I built a mobile-friendly GOTV web application based on a prototype built by Jacob which our volunteers across the city used to input the data from the bingo sheets as they got them from the polling stations. This was a big upgrade over previous campaigns, where the sheets had to be physically transported to a nearby location with a computer for input. Having a single app for the whole city made it possible to centralize data collection and decision-making in a way which would otherwise have been quite difficult.

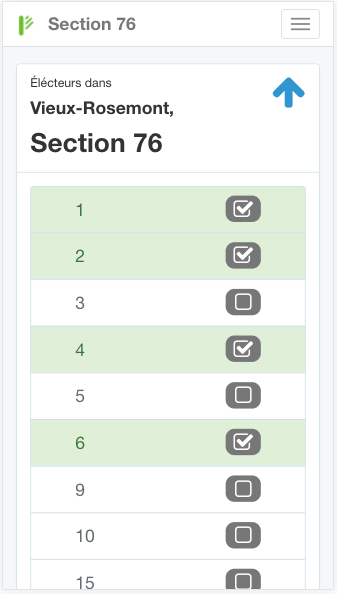

The week before the election, volunteers entered in data from a 7-inch-tall stack of sheets from early voting polling stations, and between that and election day, over 300 volunteers used this app to enter in bingo sheets. Here is a screenshot of the app on a phone: volunteers just selected a district and polling station and ticked off the sequence numbers from the bingo sheet:

The data-input part of the GOTV app

The data collected through the GOTV app was linked in real time to the canvassing and DGEQ lists, allowing it to be used both tactically and strategically throughout the day.

Tactically, every 15 or 30 minutes I would export the phone numbers of our supporters whom we knew had voted and uploaded them to a central Do-Not-Call list, so that our auto-diallers would not connect our hard-working phone bank volunteers to people who had already voted and waste everyone’s time.

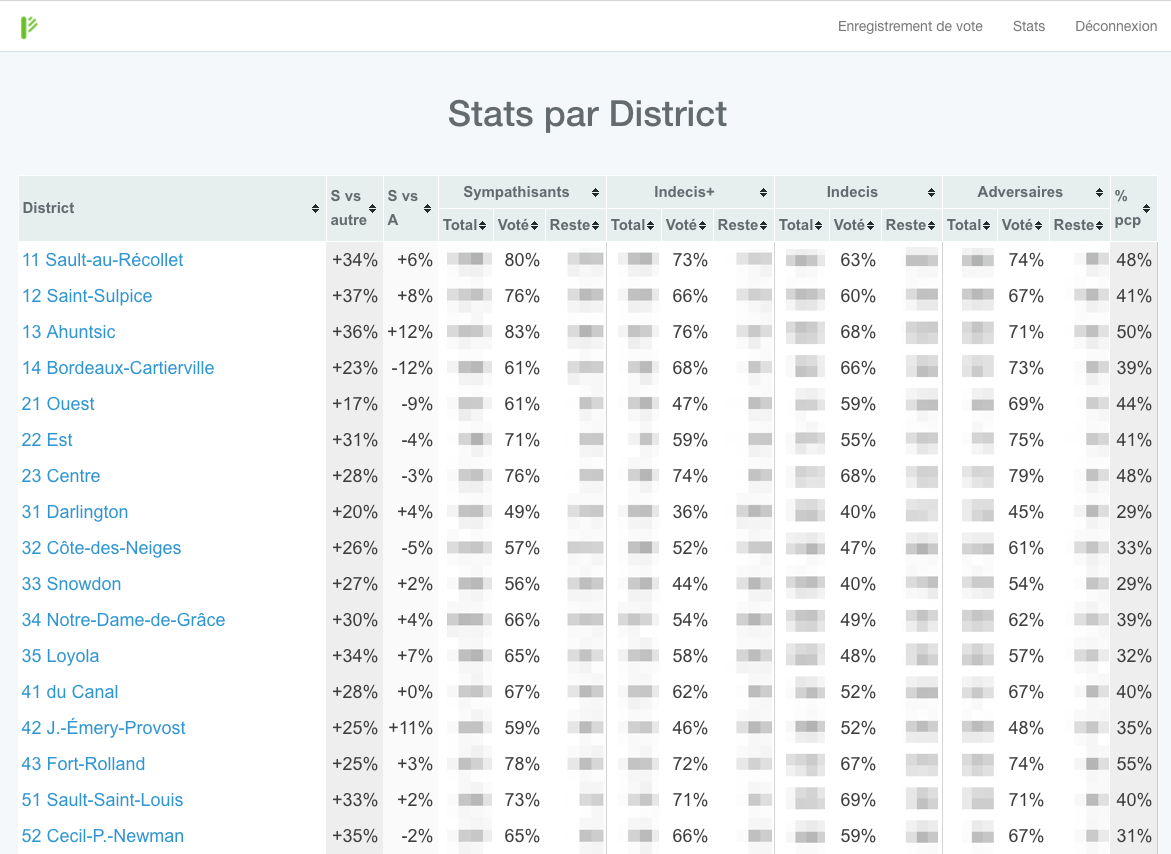

Strategically, the app featured a city-wide, district by district dashboard which gave us an near-real-time view of where our supporters were coming out to vote or staying home, and even were our adversaries were doing well, because some of our canvassing had identified electors who definitely were going to vote for someone else than Projet Montréal. Jacob and the rest of the campaign staff were able to use this dashboard throughout the day to prioritize which districts were going to be next in the phone-bank queue, and where volunteers should be doing door-to-door GOTV, so as to keep focussing our energies on phone lists and areas which had many remaining supporters who hadn’t voted yet.

Below is a screenshot of what our dashboard looked like: it’s a re-orderable table with many columns. After the last election, I became known for my electoral results maps and graphics, but in this case a visual representation of the geography was less important than the numbers, as everyone involved knew each of the 58 districts by name, so we stuck with tables. The columns were carefully chosen to provide the most useful information: ratios of how well our supporters were turning out compared to the population at large or compared to our adversaries’ supporters, as well as the remaining number of supports to turn out, etc.

The dashboard part of the GOTV app with some numbers blurred out

Post-Mortem and Conclusions

Unsurprisingly, I was thrilled at the results of the election when they were announced, and I was happy and proud to have contributed my skills to what was a huge effort by many talented and motivated volunteers and staff. I really enjoyed learning about all the nitty gritty details of how election-day campaign activities unfold, and it was a lot of fun to design and build a complete data-collection and reporting system in such a short time-frame for such a clear, focused and worthwhile purpose.

On a more self-critical note, the app I built and the processes we used held up during election day, but not without hiccups. Our biggest issue was in understanding which specific hours’ bingo sheets had been entered and which hadn’t, which the app didn’t track explicitly, so there was some uncertainty about which numbers we were looking at at various points in time. We also clearly fell a bit behind in entering in the data, and by mid-afternoon we had come up with the idea of just having volunteers send us photos of the bingo sheets via Slack so more people could help with data entry. The next time I help with GOTV, I think I would favour a process whereby data entry happens on laptops in “data-entry banks” (by analogy to phone banks) on a bingo sheet checklist basis so we would know which had been recorded, with the runners in the field just needing to upload photos rather than doing data entry on phones.

Finally, did my efforts make a difference? I think my contribution, like most volunteer contributions to large efforts, was to save time, money and energy for staff like Jacob who would otherwise have spent days during the campaign fighting with huge lists in Excel and precious hours on election day collating data by hand – or paying fees to companies who sell these types of services – and instead enabling them to focus on higher-value, more strategic concerns. Getting out the vote is a critical part of any campaign, and can make a big difference when things are close. In this case some of the smaller races were quite close, so maybe we did impact the outcome. Overall, though, we won with a comfortable margin in many places, which means that Mayor Plante and Projet Montréal have a strong mandate to run the city for the next four years, and I’m looking forward to the initiatives that they will push forward to improve the quality of life of all Montrealers.

⁂